Welcome to “A leer, carajo” a corner of this blog dedicated to highlighting the work of artists of or adjacent to the Venezuelan diaspora 📚.

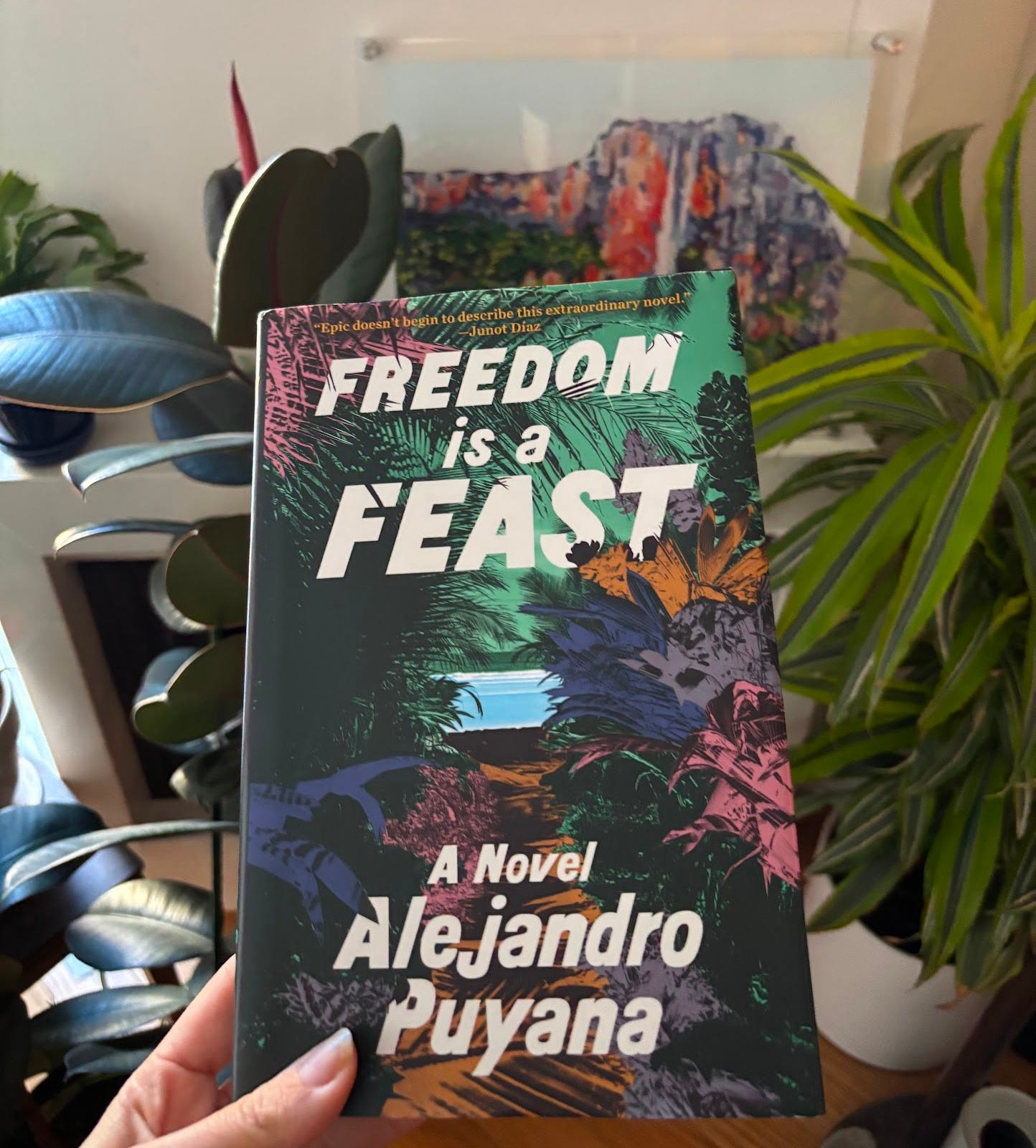

For our first-ever book in the series, I’m excited to talk about Freedom is a Feast, by Alejandro Puyana (Little, Brown & Co, 2024), out in hardcover, but coming to paperback this summer!

I heard an incredibly smart writer once say that writing isn’t about finding answers but holding questions1. I think that’s a good framework for talking about this book2.

Freedom is a Feast holds the question of how the personal evolves as the political devolves. The book chronicles the times of Stanislavo, a “white city boy” fighting in the guerrilla movement in the jungled beaches of Mochima in western Venezuela in the late 60s. He falls in and out of love with the movement and Emiliana, a fellow revolutionary, before he leaves Venezuela. Fast-forward 40 years, and we’re in the 2000s in the Caracas barrio of Cotiza, where María lives with her son Eloy3, who was wounded by a stray bullet during that coup. Stanislavo is back, now a respected journalist chronicling the rise and fall of Chavismo. Chávez comes and Chávez goes while everyone must reckon with their personal choices.

Alejandro Puyana is a Venezuelan writer who moved to Austin, TX, at 26. In interviews, he discusses his writing throughout his life as a college student in Venezuela and after coming to the States for an advanced degree in Marketing. He’s published both short stories and nonfiction about his experiences in Venezuela (links at the end).

The first thing I loved about this book was the cover. I’m a sucker for the big bold font and the color-blocked images depicting the jungled beach. Puyana mentions in the acknowledgements that it was designed by Michu Benaim and Lope Gutiérrez, also Venezuelan. We love to see it.

I was struck by the book’s dedication: to Teodoro Petkoff. I recognized his name as someone from the political comings and goings of my youth in Venezuela, but I knew little else about the man with a mustache and glasses that had a newspaper that didn’t like Chávez. But, like the dedication says, his real story is hard to believe.

Petkoff was the son of European emigrants, his father Bulgarian and his mother a Pole of Jewish origin. Having been imprisoned by the right-wing dictatorship of Marcos Pérez Jiménez in the late 50s, he veered left. He joined the Communist Party at 18 and participated in the armed guerrilla movement of the 60s against the Venezuelan government. Puyana grew up listening to those stories; Petkoff was a family friend. Puyana’s novel takes inspiration from Petkoff’s frankly incredible stories, like his famed escapes from prison.

Petkoff was not a zealot. “Only fools don’t change their minds,” he said. After the Soviet Union invaded Czechoslovakia in the late 60s, he left the guerrilla. Castro called him a traitor; Breznev called him a heretic. He was also friendly with Gabriel García Márquez? I told you, this guy’s story is incredible. He worked in government and had several unsuccessful presidential runs4. Even though he leaned left, he was a vocal Chávez critic. He founded the newspaper TalCual in 2000, which won him lots of acclaim abroad and loads of trouble at home. He died in Caracas in 2018 at the age of 86.

I’ve spent many sentences describing this politician’s life, and you may wonder why. Yes, Stanislavo goes through a similar journey: from guerrillero in the 60s to journalist in the 2000s. But every character in this book is imbued with a petkoffian drive for progress and a necessity for reinvention as their Venezuelas fall apart. Not in a hokey and naive way where they bootstrapped through with love and hard work, but more a rugged determination that these characters earned and unearned through blood, sweat, and tears (literally).

“Venezuelan people live their lives in a political way,” Puyana mentioned in an interview. He does an incredible job at making that come to life. The political goings-on permeate every character’s decisions. In the back half of the book, Chávez dies (spoiler alert!) as María deals with a family situation. It is such a chaotic moment, and she is so over being swept by the tides of history that she exclaims: “Nobody cares” about her and her family, “Nobody cares except me.”

These are characters beyond caricature. They are rendered with complex desires and motives. To do this effectively, the author has to inhabit characters that they disagree with: the sifrina Señora Romero who treats María poorly as her maid; Wili, Eloy’s spiritual brother who leads both of them astray; even the main characters of María, Eloy, Emiliana, and Stanis have their unsavory moments. To me, this book makes the case for fiction as a healing practice for modern-day Venezuelans. In fiction, you have to look at individuals who embody those who have hurt you and reconcile the hurt they’ve participated in with the humanity within them. That is hard to do. Sometimes, it’s straight-up impossible5. However, the only way to build a future as a diaspora is to start with a shared sense of humanity. In that sense, this book is not a retelling of horrors, but a deeply hopeful narrative. Because if there is humanity within most of us, then that is a starting point for us to build a shared future on.

Puyana is impeccable in his presentation of Venezuela as a place, both in the details and the vibes. He achieves this in part by doing a lot of traditional research and getting facts precise. But he also throws in a lot of deep-cut specifics6. Whiskey is never just whiskey: it’s White Label, Black Label, Old Par, or Buchanans. Each a different signal, perceivable to the trained reader. He writes out the protest chants of “Chávez, amigo, el pueblo está contigo.” The Romeros, who Maria works for, sifrinos as they are, don’t just have plates…. they have Royal Copenhagen china.

You might also ask, “How will the vibe be right if the book is written in English?” Fair, but you’ll be glad to know there is a lot of Spanish. And I mean dialogue beyond referring to someone as “mami” or “abuela.” The language is very carefully placed throughout the book to invite non-speakers in and make native speakers feel more at home.

Alright, I will stop. I could keep writing about this book all day, but you have a life to live after this post.

Look, I really liked it. I think you will too, even if you’re not from Venezuela. All of the reviews I could find online are positive, if not glowing. Publishers Weekly calls it impossible to put down. There are so many blurbs (quotes from other writers used to promote books) from such incredible writers singing this book’s praises7, and none are Venezuelan. So, if you think I’m too biased, listen to them, not me.

For those of you who know me, get excited because you’re getting a copy of the paperback for Christmas. And then you’ll get the additional gift of having to talk to me about it.

Additional Reading / Listening:

An episode of MFA Writers with Jared McCormack, a podcast on… You guessed it: writers! A really interesting listen where Puyana talks about his writing, the book and its transformations, and the publishing process.

Bookmarks (a collection of book reviews) for Freedom is a Feast

Puyana's short story “The Hands of Dirty Children”, featured in the 2020 volume of The Best American Short Stories

Puyana’s short non-fiction piece in Tin House, “I Can Smell The Tear Gas From Across The Sea”

A very recent interview with Puyana in El País in English and Spanish

Why are you doing this book review stuff?

I’m ashamed to say that I had not heard of this book until late last year. It came out last summer amid the presidential struggle, protests, and everything else happening in Venezuela. I say that, and it sounds like an excuse, and maybe it is. It felt like my brain was seeping through my ears in August; I had no idea what was going on in the world, much less literary spaces. But finding this book so late in the game was also a lesson: we/I must do better. The expletive in this column's title reminds us that we/I can do better, carajo. If the diaspora isn’t going to toot its own horn, no one will. We are each other’s cheerleaders, no matter where we are or in what language we write.

So I’ll do these once a quarter, meaning the next book will come sometime in the summer. I still haven’t decided on the next one, so if you have any suggestions, I’d love to hear them!

👋

And about so many things more broadly

Can you forgive the man who held you hostage at gunpoint? The military general who sold your future down river for his own gain? Those are the questions this novel is holding.

He mentions things like Fresh Fish! Ey, los que saben, saben.

Junot Diaz, Luis Alberto Urrea, Elizabeth McCracken, Kali Fajardo-Anstine, Laura van den Berg

it's not in English but may I suggest: Atrás queda la tierra by Arianna de Sousa?